The trip that Edward Bellamy took to Germany with his cousin is well documented as being one of the reasons he became interested in social reform. Less well-known, however, is that he took another long journey with a family member in the 1870s—to Hawai‘i. What might that trip have been like?

In early 1878, Bellamy and his brother Frederick traveled to Hawai‘i1 with the goal of improving their health.2 At the time, the group of islands was still its own independent country, ruled by King Kalākaua, but their culture was very different from what British Captain James Cook found a century before.

American missionaries arrived on the islands in 1820, not long after the Hawaiians decided to abandon their religion. Consequently, Christianity caught on more readily than it otherwise may have. The missionaries established schools and a seminary, and they helped Hawaiians develop a written language and achieve the highest literacy rate in the world.3

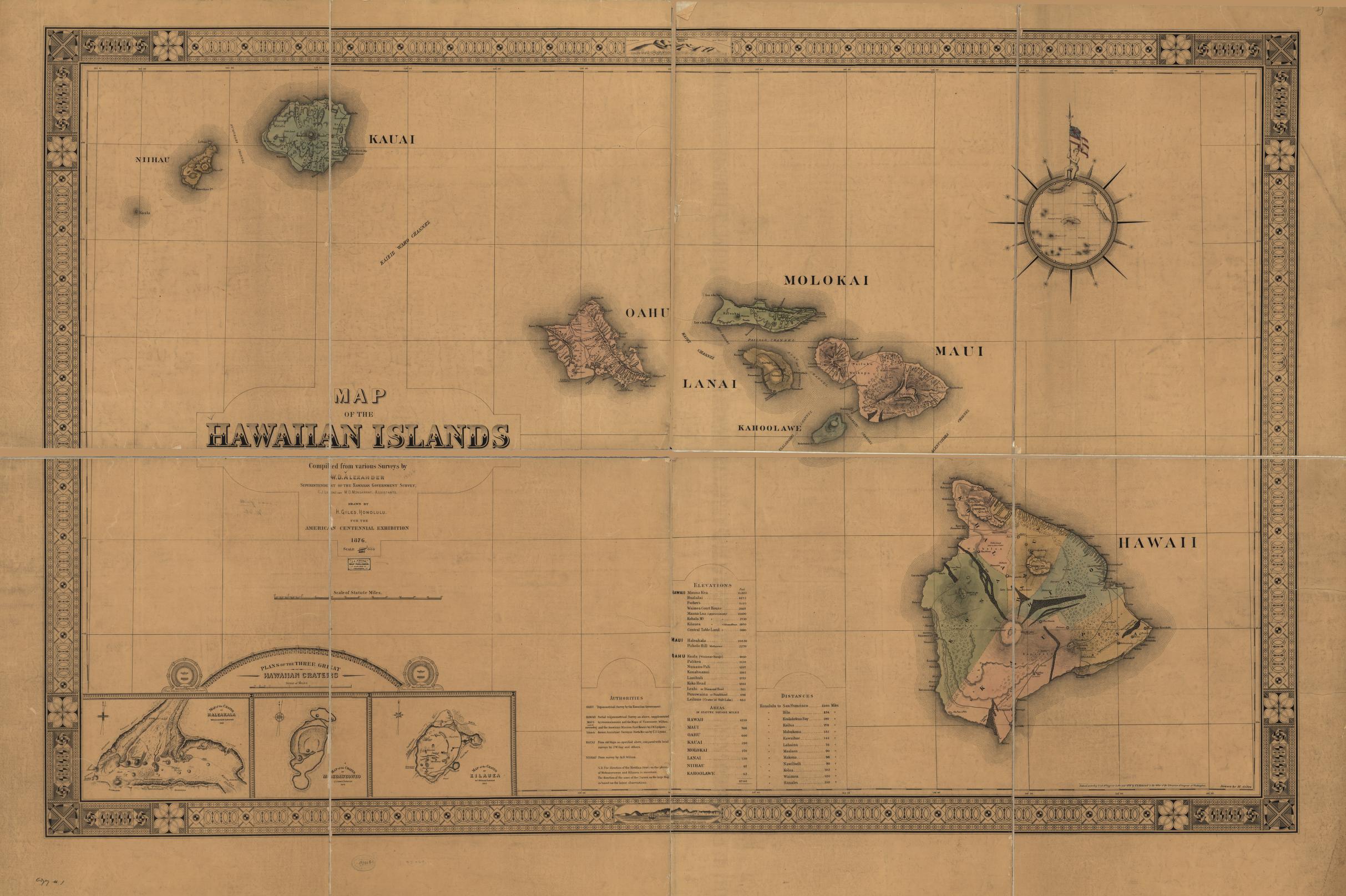

1876 Map of the Hawaiian Islands by H. Giles. Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, 2003627047

When the Bellamy brothers visited, sugar was a rapidly growing industry. While not native to Hawai‘i, it became as important to the economy as whaling had been in the decades before; exporting only 300 tons of sugar in 1851, the amount grew to 31,800 tons in 1880. To keep up with demand, laborers were brought in from China and Japan, adding to the cultural complexity of the islands. In 1878, total residents numbered just under 58,000, and the number of native Hawaiians was declining. The racism that existed in the United States was also far more prevalent on the islands than it had been fifty years before.4

Among Bellamy’s surviving papers is a notebook identified as the Hawaiian notebook. However, he used the notebook to jot down thoughts, general observations, and story ideas rather than as a travel journal. A letter that he wrote to his brother Charles before departing from San Francisco provides almost no clues about his itinerary, as he starts off discussing business and only vaguely references the next leg of his journey. A second letter, written from San Francisco on his return, is even less informative, telling his parents of his and Frederick’s plans to travel home by train (rather by sea, as they had on the way there), observing that California “grows on one” the longer one stays, and stating that they had both gained weight on the trip.5

Coral stick pin that belonged to Edward Bellamy. This pin may have been a souvenir from his trip to Hawai‘i.

The richest source of information about these few months of Edward’s life is his daughter, Marion Bellamy Earnshaw. In her unpublished memoir, she describes the fascination she and her brother had for the souvenirs her father had kept—“Sweet smelling, carved sandalwood boxes filled with necklaces and bracelets of wooden beads, strung with bright blue beads at intervals” that he had brought back for her mother, and a piece of hardened lava containing a few coins that the brothers had tossed in when they visited the erupting volcano Kīlauea. She also mentions an unverified but exciting family story that Edward and Frederick prevented a mutiny on the ship to Hawai‘i!6

Bellamy didn’t talk about his visit to Hawai‘i in the same way that he discussed how his experiences in Germany influenced his work. However, that’s not to say that he didn’t draw from this second trip and incorporate it into his fiction. In 1880, a short story titled “A Tale of the South Pacific” appeared in the magazine Good Company, which was published in Springfield.7 Regardless of where he went and what he saw on his visit to the islands, it likely made a lasting impression. As he wrote in his January 15 letter to Charles: “Before leaving home I should have said that a young man anxious to see strange and interesting things had far better travel in Europe than where we have come. But I doubt if I should say the same thing now. This is a mighty odd and mighty interesting country and we are going to one still more so.”8

Notes

- Bellamy wasn’t the only well-known writer to visit Hawai‘i in the 1800s. British novelist Anthony Trollope passed through on his way from New Zealand in 1875. And almost a decade before, in 1866, Samuel Clemens went there as a reporter for the Sacramento Union (James L. Haley, Captive Paradise: A History of Hawai‘i, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014, 204, 226).

- Sylvia Bowman, The Year 2000 (New York: Bookman Associates, 1958) 41.

- Haley, 91-3, 281.

- Haley, 208-10, 212, 260, 262, 280; Hawai‘i Censuses: Historical Censuses, https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/c.php?g=105181&p=684171 (accessed August 17, 2024).

- Arthur E. Morgan, Edward Bellamy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1944) 58-61; Edward Bellamy to Charles Joseph Bellamy, January 15, 1878 and Edward Bellamy to Rufus King Bellamy and Maria Louisa Putnam Bellamy, April 4, 1878, MS Am 1181 (27-29) Bellamy, Edward, 1850-1898. Correspondence, 1850-1898, Houghton Library, Harvard University, https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:fhcl.hough:5312299 (accessed August 18, 2024).

- Marion Earnshaw, “The Light of Other Days,” n.d., Marion Bellamy Earnshaw Collection, 118-9.

- A scan of the full story is available through Hathi Trust: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015013138881&seq=18

- Edward Bellamy to Charles Joseph Bellamy, January 15, 1878.

Edward Bellamy House

Edward Bellamy House